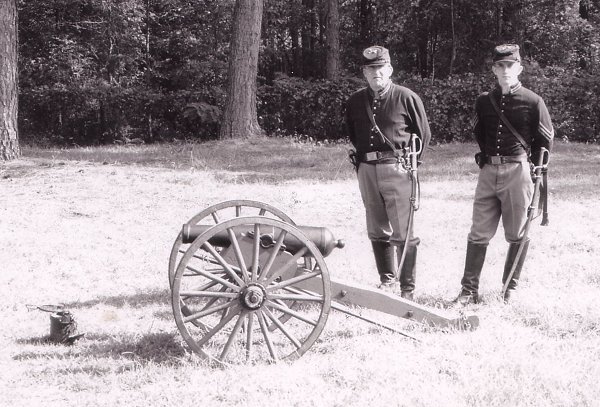

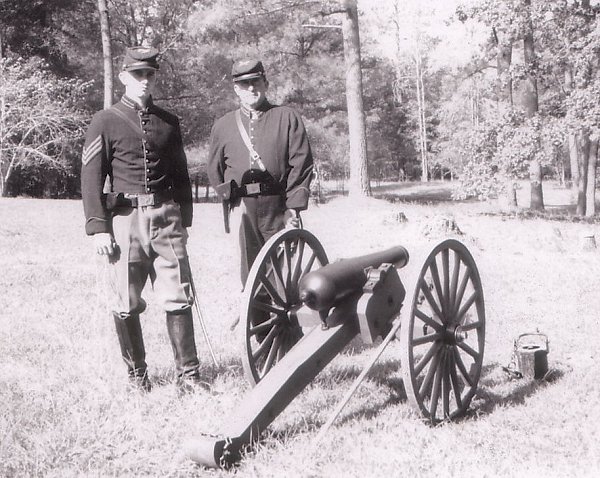

This very rare Woodruff Gun was likely in service with 4th Iowa Volunteer Cavalry, which ended the Civil War era in Macon, Georgia. It was cast by Greenleaf Foundry in Illinois in 1861. Only 35 (possibly 40) Woodruffs were produced total and apparently as few a 5 Woodruffs exist today

Development of the Woodruff Gun

(by Ralph Lovett)

The Woodruff skirmish gun might be most easily compared to the Model 1841 Mountain Howitzer. In general size, weight, and employment they are essentially the same. However, it is important to note that the Woodruff is a gun, not a howitzer, and for this reason fired a more flat trajectory. Also, their projectile weights differed greatly, with the mountain howitzer having a ten-pound advantage.

The small twelve-pounder M1841 Mountain Howitzer served quite well in the pre-Civil War period of expansion into the West, warfare with nomadic Indians and the Mexican Army. The little mountain howitzer was extremely mobile and could easily be ". . . carried up steep ascents, and to the tops of flat-roofed houses, in street-fighting."1 After all, its tube weight was only two-hundred twenty pounds.2 It performed extremely well against Indians from Florida to Kansas. The real secret to the enormous success of this small howitzer was its employment only where there was little chance of counter-battery fire. In both examples of its use the mountain howitzer had no real competition on the field, as neither the Indians nor Mexican Army possessed any real artillery threat. When the Civil War began it became increasingly apparent that the limited range of the mountain howitzer (range 1005 yards with a shell or 800 yards with grape and canister) would preclude it from affective use on the battlefield.3 The Civil War was generally

fought with larger weapons, such as the 12 Pounder M1841 Field Howitzer (range 1072 yards) and the ten-Pounder Parrott, (range for 2.9 inch Parrott, 3200 yards or 4400 with the 3.67 inch shell).4 However, small guns still had their die-hard supporters. Among one of these avid supporters was James Woodruff. His scheme to have Greenleaf Foundry cast two-pounder guns for supporting cavalry was quite impractical. He had no prior experience in designing or manufacturing of weapons. In fact, his only real military affiliation was as provost marshal for the Quincy, Illinois Congressional District. But he did have important connections in government. The real reason for the acceptance of the Woodruff into Federal service was politically motivated. Upon the outset of the war, James Woodruff liquidated his carriage company and took a job in government. The little Woodruff two-Pounder was his brain-child.

It was with a bit of arrogance that Woodruff wrote directly to Brigadier General James W. Ripley, on 6 October 1861:5

I submit herewith a description of, and propositions for furnishing light Cannon, known in the West as the ` Woodruff gun'. They are manufactured from the best charcoal scrap iron, faggotted, brought to a welding heat, and forged, and thoroughly compacted under a heavy trip hammer, then turned, bored, and polished. Their length is 3 feet, the bore is 2-1/8 inches, which just allows the chambering of seven lead ounce balls in the canister, the canister which have been generally used with them have contained 42 lead ounce balls. The carriage part is made light, but strong, and all the materials and workmanship are of the best quality. Each gun is thoroughly proved before it leaves the factory. The weight of each Gun is about 256 lbs. They are accurately sighted, and at repeated trials have proved themselves effective with round

ball at 1-1/4 miles, and with canister their most effective range is about 700 yards...

General Ripley flatly rejected the Woodruff gun, seeing no realistic place for it within the Federal arsenal. Following the rejection of the Two-Pounder, James Woodruff began calling on the help of his political contacts. Governor Richard Yates arranged for an audience with President Lincoln. Resulting from this meeting Abraham Lincoln wrote Lieutenant General Winfield Scott the following letter (scribbled across the document of refusal from General Ripley):

"Will Lieutenant General Scott please see Mr. Jas. Woodruff, and in consideration of all the grounds say whether he would advise the purchase of the guns as proposed?"6

On receiving this letter General Scott reacted just as Ripley had, with a quick rejection saying "I concur fully with Brigadier General Ripley in the opinion he has expressed within this subject."7 After this failure James Woodruff once again approached the President, accompanied by Governor John Wood, the ex-governor of Illinois. This time the note to the Chief of Ordnance was some what more direct. In early November Lincoln wrote:

"Please see Gov. Wood and Mr. Woodruff, bearers of this,

and make the arrangements for arms which they desire if you possibly can. Do not turn them away lightly; but either provide for their getting the arms, or write me a clear reason why you can not."8

Action was immediately taken by Ripley to incorporate the Woodruff into the Federal Army. The official Congressional Records read:

Ordnance Office Washington

November 15, 1861

Contract With James Woodruff

Sir: By direction of the President of the United States I give you an order for thirty Woodruff guns, to be furnished to Colonel Cavanaugh, of the 6th cavalry regiment, Illinois volunteers, for the use of the Governor's Legion, provided they cost no more than two hundred and eighty-five dollars ($285) each, mounted and equipped as per specifications filed by you in this office, dated 6th October, 1861...9

It was the apparent intent of this document to tie the Woodruffs with the 6th Illinois Cavalry, which was formerly at Shawneetown. Woodruff had proposed arming this unit with nine thousand Belgian sabers (in the St. Louis Arsenal), one thousand five hundred Navy Colt revolvers and one thousand five hundred rejected Cosmopolitan carbines. It would appear that possibilities concerning these unissued weapons, the availability of the Woodruff guns and the existence of an unarmed volunteer unit in Shawneetown was how Woodruff based his proposal to Lincoln. It also seems apparent that little concern for the quality of the weapons was given by Woodruff or the President. The only real consideration boiled down to, a volunteer unit enthusiastic about getting into the conflict had to be armed with something or not get a chance to fight. Of course, this was the sentiment in quite a few militia and volunteer units, but few such units had the patronage of someone so high in government. Even though the wording of the Congressional Record, concerning the thirty Woodruff guns would seem to link them with the 6th Illinois, this was not the case. In fact, no records have been unearthed indicating the 6th Illinois actually received any of the Woodruffs. However, records do exist that place the Woodruffs with 10th Illinois Cavalry, 2nd Iowa Cavalry, 4th Iowa Cavalry and 1st Illinois Light Artillery Battery K.

The first documented mention of the Woodruff gun in combat is from the November 10, 1862 report of Captain Hiram E. Barstow, 10th Illinois Cavalry. Company C, under his command, was pinned down near Clark's Mill, Missouri. The entire company surrendered to the Confederate force under J. Q. Burnbridge. About the engagement Captain Barstow said: "If I had known at the outset that they had artillery of that size I should have abandoned the post when I returned from driving in their advance."10 This comment implied that Captain Barstow was well aware of how ineffective his little two-Pounder Woodruff was against even comparatively small six-pounders that were employed by the Confederate cavalry.

On Colonel Benjamin Henry Grierson's Raid into Louisiana, in which 2nd Iowa and 1st Illinois Light Artillery participated, the little Woodruff gets slightly more favorable reviews. On 20 April, 1863 Major Hiram Love, of the 2nd Iowa, placed Captain Jason B. Smith in charge of one of the two-pounder Woodruffs. 11 On 21, April 1863, Colonel Hatch's 2nd Iowa moved a two-pounder into position within a hedged lane near Palo Alto. In reference to this piece it is stated in Grierson's Raid that Barteau (the Confederate

commander) ". . . may have underestimated the frightening effects of the two-pounder cannon. . . . ."12 Despite this statement, it is also pointed out that "If, instead of halting for noon feeding, the Second Alabama cavalrymen had galloped forward to Palo Alto with their three pieces of artillery to reinforce Barteau's men, Colonel Edward Hatch's predicament would have been grave indeed."13 Apparently Captain Jason Smith did at some point acquire three more Woodruff guns to make a total of four. 22, April 1863 on the road to Louisville "One of the gun carriages collapsed."14 It was dismantled and lashed to the back of a mule. Also on 5 May 1863 Grierson, Colonel Edward Prince, Major Mathew Starr, Lieutenant Samuel Woodward and two privates went aboard a steam ship in Baton Rouge to have the Woodruffs repaired in New Orleans.15 This trouble was probably due to Woodruff not using a proven carriage type for his invention. The carriages were constructed by Battle and Boyd, of Quincy, Illinois. No examples of this carriage are known to exist today but considering one simply "collapsed" and the others later required repair, it should be safe to assume they were not well constructed. This is yet another area were the Woodruff fell far short of the performance standards set by the Prairie and Mountain M1841 Howitzer. On 1 May 1863, Colonel Prince placed two of Captain Smith's Woodruffs in support of A and D Companies, in the immediate area of Wall's Bridge. Here the two Woodruffs helped repel Major De Baun's Confederates. However, as in every case of successful use of the Woodruff, there was no artillery to counter the Woodruffs.

In reports of the 10th Illinois Cavalry in May 1863 ". . . the two battalions were at Pilot Knob. . . . Here the two-pound howitzers were exchanged for two twelve-pound mountain howitzers."16 The 10th Illinois Cavalry had six Woodruffs and apparently all ended up in Fort Davison in Pilot Knob, Missouri. Five months before the assault on Fort Davison Lieutenant Colonel John N. Herder gave an extremely optimistic report saying to Brigadier General Thomas Ewing, "I wish guerrillas would show themselves in force so as to give us a chance to whip them to hell from where they can rise no more."17 On 28 September 1864, the report of Major W. W. Dunlap (Army of Missouri, CSA) list six of Lieutenant Colonel Herder's former Woodruffs as captured at Pilot Knob. There is little mention of the Woodruffs in the actual fighting. This is probably due to the fort being equipped with four thirty-two-Pounders and two twenty-four-Pounders, no doubt these large pieces did the real fighting. Despite this, the logistical information given by Herder is interesting. He reports

on 15 April 1864, that ". . . the boxes belonging to caissons for the Woodruff smooth-bore guns are being altered to suit the new kind of ammunition. . . ."18 Herder later wrote ". . . the last issue of ordnance a new kind of cartridge was received not fitting the boxes, being 1 1/2 inches longer than the old ones. . . ."19 This, along with the recent excavation of Fort Davis and Thomas Dicky's Artilleryman article about its findings, provide, clear

evidence that these new cartridges were heavier, dart or minie ball-like projectiles.20 They were two-pounds fourteen-ounces with an extremely deep, wide cavity and a heavy nose designed to make the projectile fly like a dart.(The Woodruff is a smooth-bore.) It seems possible that the St. Louis Arsenal, where presumably these cartridges originated, was trying to improve the hitting power of the Woodruff. However, if this is the case no real improvement has been noted.

William Forse Scott was considerably less impressed by the performance of the Woodruff than Grierson had been. In Scott's The Story of a Cavalry Regiment, The Career of the Fourth Iowa Veteran Volunteers the Woodruffs are described, in March 1863, as being "small iron pieces, throwing a two-pound solid shot.."21 and that "they were of no value and were generally voted a nuisance. They were never known to hit anything, and never served any useful purpose, except in promoting cheerfulness in the regiment. The men were never tired of making jokes and teasing Washburn [Cyrus Washburn was the private in charge of the three woodruffs.] about

them."22 In fact, the most practical purpose the Woodruff seems to have been put to, while in the 4th Iowa Cavalry, was to serve as a cart for bringing in dead bodies.23

The Woodruff gun, despite an occasional successful engagement, was a completely obsolete piece of equipment. Its only claim to fame was that it was pressed into service with several noteworthy units and had been indirectly placed in these units by order of President Lincoln. Two of the most qualified men in Federal service, General Scott and General Ripley, went on record as being completely against its incorporation into Federal service. Their rejection could have been based on quite a few flaws in James Woodruff's plan. One, the Ordnance Department did not need to deal with the complication of production and issue of yet another type of odd ammunition. Two, the M1841 Mountain and Prairie Howitzer were generally better proven designs already within the Federal Ordnance system. Three, the Woodruff gun had a "claimed" range of two thousand two hundred yards with solid shot. This was exactly half the range of the Parrott, one of the most common guns on the Civil War battlefield. Its shell was approximately eight pounds heavier than the Woodruff's. This severely restricted the counter-battery capability of the Woodruff. It is doubtful if the Woodruff would have any real affect on advancing infantry or cavalry except when firing canister. In this role it was limited to only seven hundred yards, and its light projectile weight greatly limited its effectiveness. Even without artillery support, determined infantry should have been able to over-run Woodruff gun batteries.

The Civil War marked a real turning point in American History. It was the first war where the need for industrial technology was at least as great as the need for troops. In the case of the field artillery in 1861, technology developed to include rifled long range, large caliber guns, light enough for field service. It also saw the continued use of 1840's style howitzers that served well against infantry. Their lesser range often prohibited their use as counter-battery weapons. This was the niche for the rifled gun. The Woodruff, with its short range, non-rifled small bore, does not fit into this system. The Woodruff is left with no logical place on the Civil War battlefield; the only exception being, on the rare occasion when there was no enemy artillery to counter them. Even in the Western territories, where lesser amounts of modern weapons were available, there was virtually no place for the Woodruff. It would have made far more sense for the Federal Government to have used the funds for the Woodruff and its ammunition instead for modern rifled guns or even the M1841 Mountain Howitzer.

NOTES

1J.B. Benton, A Course of Instruction in Ordnance and Gunnery, Composed and Compiled for the Use of the Cadets of the United States Military Academy (New York: D. Van Norstrand, 1861), 175.

2Ibid.

3Warren Ripley,Artillery and Ammunition of the Civil War (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, 1970), 367.

4Ibid., 370.

5James Woodruff, Quincy, Illinois, to Brigader General James W. Ripley, Washington D.C., 6 October 1861, The National Archives and Records Services Administration, Washington.

6John R. Margrieter, "The Woodruff Gun," Civil War Times Illustrated, May 1973, p. 34.

7Ibid.

8Robert V. Bruce Lincoln and the Tools of War (New York: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc. 1956), 125.

9U.S. Congress, House. 40th Cong., 2nd Sess., Congressional Record., 1867-1868.

10"U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion; A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, ser. I, vol. 13, 356. Here after cited as O.R.; unless otherwise indicated, all references are to series 1.

11D. Alexander Brown, Grierson's Raid, (Urbana, Illinios: 1954), 56.

12Ibid., 68.

13Ibid., 69.

14Ibid., 87.

15Ibid., 227-228.

16Adjutant-General's Report-Illinois volume 8. Springfield, (1901): 255, quoted in Ken Baumann, Arming the Suckers 1861-1865 (Milan, Michigan: Morningside, 1989), 56.

17O.R. VOL. 34, PT. 3, 166.

18Ibid., 165.

19Ibid.

20Thomas S. Dickey, "Evidence Shows that Woodruff Gun Used a Conical Projectile," Muzzleloading Artilleryman, Spring 1985, 27.

21William Forse Scott The Story of a Cavalry Regiment, the Career of the Fourth Iowa Veteran Volunteers (New York: The Knickerbocker Press, 1893), 62.

22Ibid.

23Ibid.

The Lovett Collection is looking for any photographs that show the correct carriage for the Woodruff Gun